3ppm Tax on Electric Cars: A Fair Step or a Flawed Start?

The government’s proposed 3 pence-per-mile tax on electric vehicles has caused predictable noise, but the principle behind it shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone. We’ve always known that EVs would eventually contribute to the public purse in a way that replaces lost fuel duty.

Road maintenance and infrastructure still need funding, and as petrol and diesel usage falls, that money has to come from somewhere.

However, accepting the principle and accepting the plan are two very different things. The proposal in its current form contains several issues that deserve scrutiny, especially if the goal is to design a fair, workable, future-proofed system.

No allowance for EU mileage

Many UK drivers regularly take their EVs across to France, Spain, Germany, and beyond. Under the current 3ppm proposal, there is no mechanism to remove EU mileage from the taxable total. A driver could easily accumulate thousands of untaxed miles abroad, only for those to be charged as if they were driven on UK roads. In some cases, this could meaningfully distort the tax burden, especially for those who tour Europe or spend long periods driving overseas.

No charge on EU drivers using UK roads

Similarly, EU drivers entering the UK in EVs would pay nothing at all. While UK EV owners face a new per-mile charge, equally heavy or heavier vehicles from outside the country could use the same roads for free. This mismatch risks being seen as unfair and undermines the principle that road usage, not nationality, should determine contribution.

High susceptibility to fraud

Mileage-based taxation sounds simple until you try to enforce it. The UK already has long-standing issues with mileage “clocking” on used cars. EVs introduce an additional layer: mileage blockers designed to prevent mileage from being recorded at all. These devices are not niche or theoretical; they are widely used across Europe and extremely difficult to detect without a forensic inspection. If mileage becomes a taxable commodity, the incentive to manipulate it grows dramatically, and some people will go to the ends of the Earth to avoid tax. Without robust verification systems, the entire tax could become utterly porous.

A built-in unfairness for PHEV drivers

Plug-in hybrid drivers sit in an awkward middle ground. They already pay fuel duty for every litre of petrol they use, yet under the current proposal they would also pay the EV mileage tax for the portion of their driving performed on electricity. In practice, many PHEVs are driven primarily as petrol cars, either due to company-car policies, poor charging access, or simple convenience. Others are driven almost entirely on electricity. But the proposal makes no distinction, creating a scenario where PHEV owners could easily end up double-taxed for the same journey.

The real cost per mile

To put this all in context, it’s useful to compare what this tax looks like in the real world.

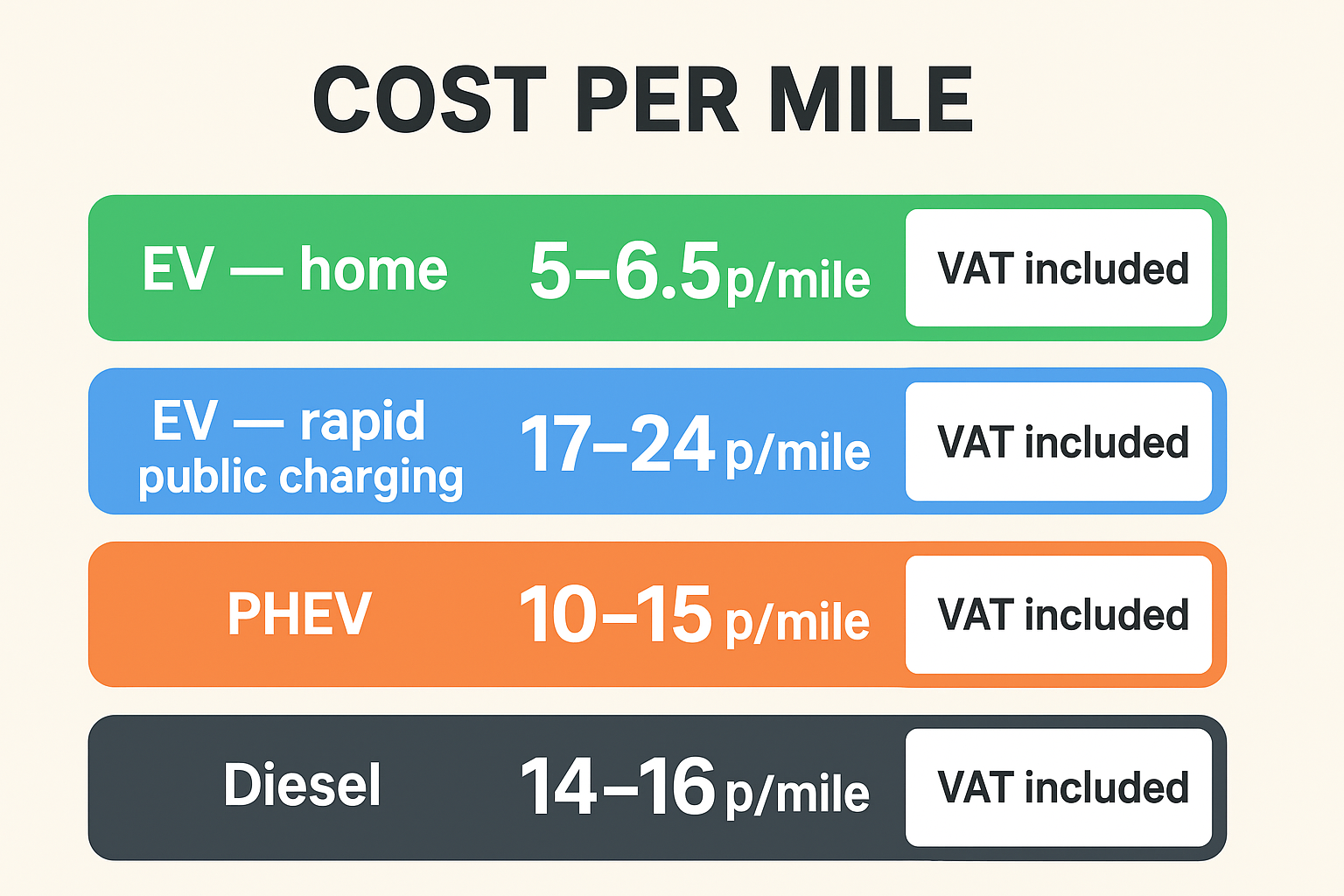

A snapshot example of how the 3ppm on EVs could affect the true cost per mile (according to current pricing)

1. Petrol and Diesel — VAT already included

Fuel prices advertised at the pump already include:

Fuel duty (fixed per litre)

VAT at 20% on top of the total (fuel + duty)

2. EV Home Charging — VAT at 5%

Domestic electricity used for home charging is taxed at:

5% VAT (reduced rate)

If we assume:

7–12p/kWh overnight tariff (these prices already include VAT in most consumer tariffs)

3.5 miles/kWh efficiency

Then the real cost per mile stays:

≈ 2–3.5p/mile for electricity

+ 3p per mile tax

= 5–6.5p/mile total

3. EV Public Charging — VAT at 20%

Public charging is charged at:

20% VAT (same as petrol/diesel)

Most displayed public charging prices (50–75p/kWh) already include VAT

Even with the proposed EV tax added, home-charged EVs remain significantly cheaper to run per mile, while public-charged EVs begin to converge with petrol and diesel costs.

Any policy aimed at fairness should recognise this spread rather than treating all EV miles as identical.

4. PHEV — How the cost-per-mile is calculated

PHEVs use two energy sources: petrol (with fuel duty + 20% VAT) and electricity (5% VAT at home, 20% on public chargers).

Real-world usage varies dramatically: some drivers do almost all short trips on electricity, while others rarely or never plug in.

Most independent testing shows typical PHEV economy between 35–55mpg once the small battery is depleted, meaning their petrol cost per mile often mirrors a medium petrol SUV.

When driven in electric mode, the cost per electric mile mirrors an EV’s electricity cost, but this represents a small portion of total mileage for many drivers.

Combining these real-world behaviours creates a typical blended cost of 10–15p per mile, with VAT included.

A plan with more questions than answers

Even setting aside the structural issues, there is the basic challenge of how the tax will be recorded, verified, and collected. So far, there is little clarity. In a recent BBC interview, even the Chancellor struggled to explain how the system would work in practice.

Given that the tax isn’t scheduled to be introduced before 2028, the government appears to have time to refine (or possibly rethink) the idea. But without a credible enforcement mechanism or a fair treatment of cross-border mileage and PHEVs, the current version looks more like a placeholder than a finished proposal.

A sensible wait-and-see

This policy is still years away, and the details may change entirely before implementation. EVs will need to contribute eventually, and most EV drivers accept that. The challenge is designing a system that is fair, enforceable, and reflects real-world usage. Until we see how the government plans to turn the idea into a functioning scheme, the only reasonable response is cautious patience.

Let’s just wait and see what eventually happens, eh?